With the publication of his debut novel, The Soft Exile, writer/musician Eric Kiefer ended a five-year, 12,000 mile exodus.

“Word for word, it’s not exactly what happened to me out there,” Kiefer said of Soft Exile. “But it’s about as close as you can get without becoming a confession. It’s a novel for the expatriates within us all.”

The fictional memoir draws heavily from his experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Gobi Desert region of Mongolia. During this time, Kiefer gathered the raw material and life experiences that would later become The Soft Exile.

The book chronicles an idealistic, young American’s decision to join the Peace Corps after an aborted suicide attempt. He spends two years as a TEFL volunteer in the fabled lands of the Mongolian desert-steppe, searching for redemption and an alternative to modern American life. Along the way, he constructs a low-powered radio station and tries his best to go native, all the while lusting for an answer to a question that will either doom or save everything… “What is the value of a good deed?”

CLICK HERE TO BUY THE E-BOOK AT SMASHWORDS.COM

CLICK HERE TO BUY THE PAPERBACK BOOK AT AMAZON

“After you survive with him, you’ll either come away even more inspired, or scared straight into staying in the States. Part adventure, part survival tale, and absolutely impossible to put down till you reach the end…”

– Named as one of “The Books We Loved in 2012” by The East Bay Express

Click here to read the article

*

*

“SEEKING REDEMPTION AND A JOURNEY IN CONSCIOUSNESS WITH THE PEACE CORPS”

– The South Bergenite

Click here to read the article

*

*

BOOK REVIEW AND AUTHOR INTERVIEW WITH PEACE CORPS WORLDWIDE

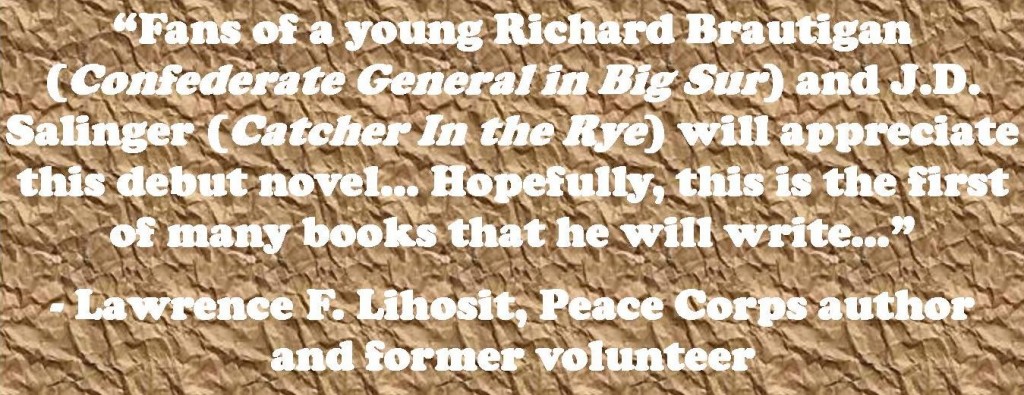

“Fans of a young Richard Brautigan (Confederate General in Big Sur) and J.D. Salinger (Catcher In the Rye) will appreciate this debut novel…”

*

An Excerpt from THE SOFT EXILE

by

Eric Kiefer

The Moving Sidewalk

The next few weeks passed slowly.

In old Mongolia, time operates like a muzzy heroin addict on a moving sidewalk. “Mongol Time” is a broken yo-yo… a bent Slinky… a deck with missing cards. It softens the reflexes at the same time it sharpens the instincts. It liquefies your day.

You wake up earlier, but slower. You stop crossing off the days on your calendar. You forget what day of the week it is. Weeks pass like broken-wing butterflies. Months disappear like soap bubbles down a drain.

And before you know it… BAM!… you’re done.

***

Pre-Service Training ended on August 12, three weeks before my twenty-fifth birthday.

When it was all said and done, here’s how my official Peace Corps resume looked: 185 hours of Mongolian language training, 50 hours of cross-cultural training, and 140 hours of ESL methodology training. But those limp compilations of numbers could only begin to hint at the real-world education that I had received in Delgerkhovd. I had spent my three months in Purgatory; I had paid my dues.

And I had smiled all the way through them.

As for the Dansarans and I, there wasn’t any teary farewell. Mongolians don’t believe in such things. But my host family and I knew the truth of the matter… in all likelihood, we’d never see each other again.

We said our goodbyes the night before I left for Ulaanbaatar, the staging point for all new volunteer departures. The cucumbers from the Dansarans’ garden had finally grown big enough to pick, and we spent a long time casually munching on these as we sat outside in the yard, basking in the glorious Mongol night. The air that night was slightly cold and snappish, like the first bite into a refrigerated apple. The stars were also particularly bright that evening, and to make conversation, Solo asked me if I knew the names of any constellations.

“Sure,” I asserted in my fractured Mongolian, my mouth full of cucumber. “But we have different names for them in America.”

I proceeded to point at arbitrary groups of stars, connecting imaginary lines with my index finger while looking up random vocabulary in my dictionary. “This is Grandma’s Triangle over there in the south. And there’s the Great Disease… the Broken Sandwich… Jimbo the Dishwasher. And there, over in the northeast, is my favorite… the Magic Toilet.”

“Yes, I can see that one!” exclaimed Little Davaa, squinting her eyes in sudden seriousness.

“If you see it, it is there,” said Solo in Mongolian, patting her daughter on the head and smiling at me.

We all sat silently for a while then, finishing off the cucumbers and listening to the sounds of the village after hours… barking dogs, crickets, and the sound of the wind in the grass. But at last the moon began to crest, and we all began to yawn. Sensing that it was time to call it quits, Solo stood up and announced that it was time to give me my “farewell gifts.”

“Oh man, that’s not necessary,” I said, trying to be polite.

Solo waved me off. “Bedgie bedgie,” she said, disappearing inside. A minute later, she emerged with a plastic bag full of presents, and the Dansarans gathered around me ceremoniously in the splendid moonlight. First, Solo dug into the bag and produced a new khaadad. She held the blue length of cloth out in her hands to me, explaining in her simplest Mongolian that the fabric represented the sky, which would always be over me as long as I lived in Mongolia.

“Bayarla,” I said, accepting the ceremonial cloth with open palms like it was a samurai sword.

When the exchange was done, Solo reached into the bag and handed me a hand-sewn Mongolian tsampt… a traditional shirt. The tsampt was a powder blue color, shiny and sharp, with delicate silver trim cascading down the hems. I turned her gift over in my hands, feeling the silky material in my palms. It was like something that a Hollywood brahma would wear.

Over the past week, I had caught glimpses of Solo making my gifts, but I was still surprised by how beautiful the craftsmanship turned out, and I told her so.

“Bayarlaa,” I told my host family, bowing slightly.

“Zuger,” Solo told me.

“Zuger,” repeated her children.

“Zuger,” repeated Chuluun.

I slept on the living room floor with the rest of the family that night, my luggage packed and piled in a heap next to me. We were hobos whiling away the night in the Grand Central subway station… hamsters scrunching in a litter pile… atoms vibrating in the same molecule.

And that was the last I ever saw of the Dansarans.

***

Back in Ulaanbaatar, the Corps finally got around to revealing our permanent assignments. Most of us had gotten what they wanted… or deserved.

Eddie had been stationed near the most iconic body of water in Mongolia, Lake Khuvsgul, with the Reindeer People of the northern tundras. Ray had been stationed in one of the local aimag centers – Mongolia’s equivalent of the “satellite city”- where he was given the task of running the English prep program at one of the city’s secondary schools. Abbie had ended up with an assignment as a community-building specialist in Khentii, a rural province in the far Eastern plains of Mongolia. Vinko the adventurer had been assigned to Baganolgii, a last-stop village near the southern Dundgobi desert-steppe. And Bridget had been assigned to a post in Ulaanbaatar, where she could teach English from the relative comfort of the city, home to so many of her vices.

As for myself, I had asked the Corps to send me to the gnarliest site they had… the “old school” Peace Corps experience. They replied by giving me an assignment in a tiny village called Mandalzuud, way out on the fringes of the infamous Gobi Desert. The way the Corps described it, Mandalzuud was a perfect microcosm of old Mongolia – rustic, rural, and even poorer than Delgerkhovd:

A population of 2,350 people and 100,000 livestock. No internet or cell phone reception. No running water. Electricity prone to blackouts. High unemployment rate. Stagnating drinking wells. No fuel, except for coal and dried dung. No jobs, except for raising sheep or drying dung.

It was exactly what I had asked for, a place where I could really make an impact. It was a place where every crappy English teacher is an instant master of foreign languages, and everyone who knows how to read the label on a bottle of Tylenol is a health expert. It was a chance to save the world, or die trying.

But more importantly, it was a chance to find the answer to the question that had brought me to Mongolia in the first place… the question that had started me on this whole two-year path to redemption … WHAT IS THE VALUE OF ONE GOOD DEED?

Because God help me, I sure as hell hadn’t found any answers in Mongolia yet.

And time was steadily running out.

***

Like what you’ve read? Watch a live reading from THE SOFT EXILE, a novel about Suicide, Mongolia, and the U.S. Peace Corps!

FOLLOW ALONG ON THE OFFICIAL SOFT EXILE FACEBOOK PAGE!